@shortridge While working tech support, I got a call on a Monday. Some VPNs which had been working on Friday were no longer working. After a little digging, we found the negotiation was failing due to a certificate validation failure.

The certificate validation was failing because the system couldn’t check the certificate revocation list (CRL).

The system couldn’t check the CRL because it was too big. The software doing the validation only allocated 512kB to store the CRL, and it was bigger than that. This is from a private certificate authority, though, and 512kB is a *LOT* of revoked certificates. Shouldn’t be possible for this environment to hit within a human lifespan.

Turns out the CRL was nearly a megabyte! What gives? We check the certificate authority, and it’s revoking and reissuing every single certificate it has signed once per second.

The revocations say all the certificates (including the certificate authority’s) are expired. We check the expiration date of the certificate authority, and it’s set to some time in 1910. What? It was around here I started to suspect what had happened.

The certificate authority isn’t valid before some time in 2037. It was waking up every second, seeing the current date was after the expiration date and reissuing everything. But time is linear, so it doesn’t make sense to reissue an expired certificate with an earlier not-valid-before date, so it reissued all the certs with the same dates and went to sleep. One second later, it woke up and did the whole process over again. But why the clearly invalid dates on the CA?

The CA operation log was packed with revocations and reissues, but I eventually found the reissues which changed the validity dates of the CA’s certificate. Sure enough, it reissued itself in 2037 and the expiration date was set to 2037 plus ten years, which fell victim to the 2038 limitation. But it’s not 2037, so why did the system think it was?

The OS running the CA was set to sync with NTP every 120 seconds, and it used a really bad NTP client which blindly set the time to whatever the NTP server gave it. No sanity checking, no drifting. Just get the time, set the time. OS logs showed most of the time, the clock adjustment was a fraction of a second. Then some time on Saturday, there was an adjustment of tens of thousands of seconds forward. The next adjustment was hundreds of thousands of seconds forward. Tens of millions of seconds forward. Eventually it hit billions of seconds backwards, taking the system clock back to 1904 or so. The NTP server was racing forward through the 32-bit timestamp space.

At some point, the NTP server handed out a date in 2037 which was after the CA’s expiration. It reissued itself as I described above, and a date math bug resulted in a cert which expired before it was valid. So now we have an explanation for the CRL being so huge. On to the NTP server!

Turns out they had an NTP “appliance” with a radio clock (i.e, a CDMA radio, GPS receiver, etc.). Whoever built it had done so in a really questionable way. It seems it had a faulty internal clock which was very fast. If it lost upstream time for a while, then reacquired it after the internal clock had accumulated a whole extra second, the server didn’t let itself step backwards or extend the duration of a second. The math it used to correct its internal clock somehow resulted in dramatically shortening the duration of a second until it wrapped in 2038 and eventually ended up at the correct time.

Ultimately found three issues:

• An OS with an overly-simplistic NTP client

• A certificate authority with a bad date math system

• An NTP server with design issues and bad hardware

Edit: The popularity of this story has me thinking about it some more.

The 2038 problem happens because when the first bit of a 32-bit value is 1 and you use it as a signed integer, it’s interpreted as a negative number in 2’s complement representation. But C has no protection from treating the same value as signed in some contexts and unsigned in others. If you start with a signed 32-bit integer with the value -1, it is represented in memory as 0xFFFFFFFF. If you then use it as an unsigned integer, it becomes the value 4,294,967,296.

I bet the NTP box subtracted the internal clock’s seconds from the radio clock’s seconds as signed integers (getting -1 seconds), then treated it as an unsigned integer when figuring out how to adjust the tick rate. It suddenly thought the clock was four billion seconds behind, so it really has to sprint forward to catch up!

In my experience, the most baffling behavior is almost always caused by very small mistakes. This small mistake would explain the behavior.

Welcome! Glad to hear the efforts are appreciated 😁

And yes, I had to spend most of today trying to make everything work smoothly... 😳

Cc @fosdem

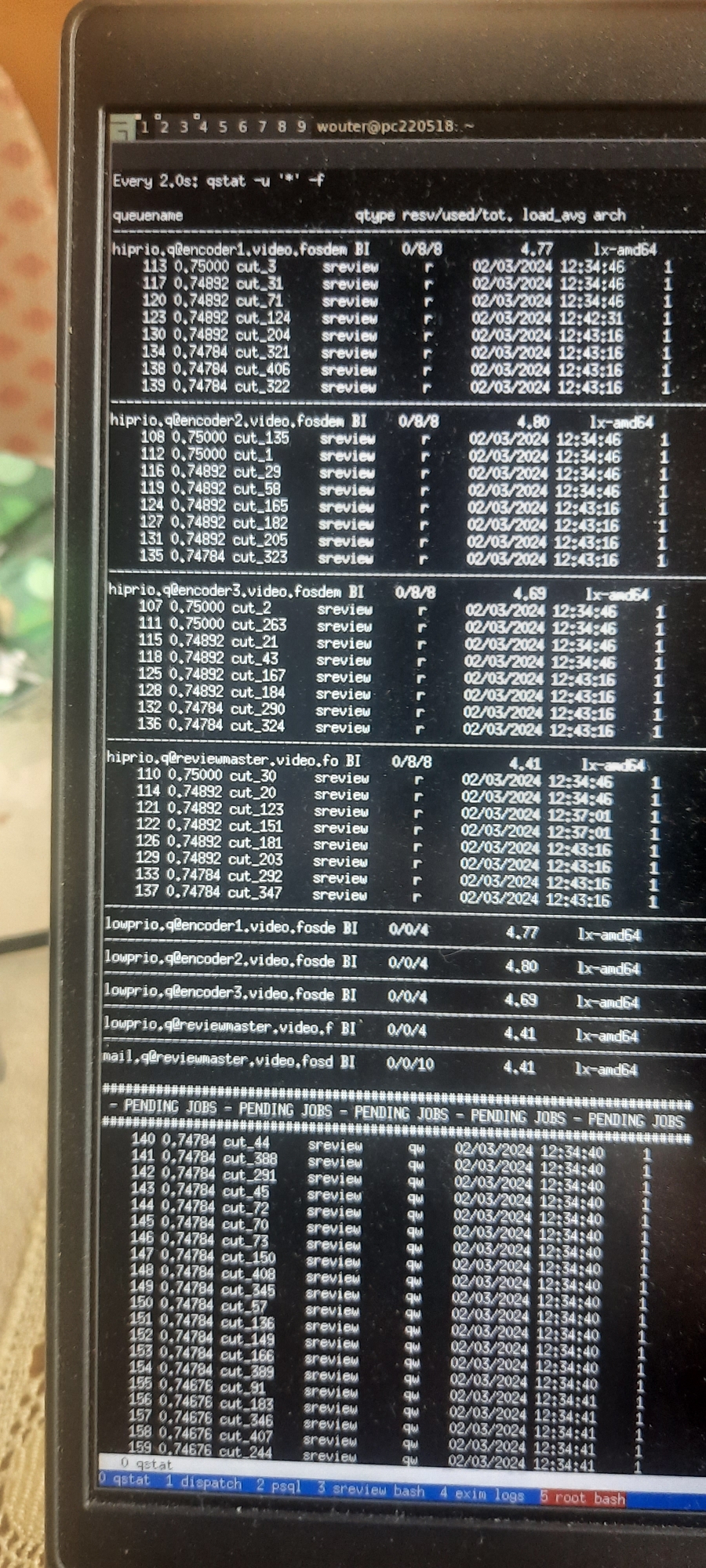

Jobs run incorrectly, and then you have to run them again... And then you get this.

😞

Baseball players

- play with wood and balls all the time

- have gotten to fourth base with their team mates more than anyone else in the world.

Like, read your audience?

Obviously there's a limit to how far you can go with this, but then I'm not advocating a model that does not even partially map onto the way things really are.

Git's data model is awesome and great and can let you do massively impressive things, but I just want to write code, you know? And I'll fall back on it when my simple model doesn't work, but for day to day things? Nah, thanks.

@b0rk

And that's fine.

What I'm saying is that I find it much easier to just Get Stuff Done if I use a mental model that is closer to how I work than it is to the actual implementation of things.

You seem to prefer the opposite.

None of this makes either you or me wrong, it just means we're different 🤷

@b0rk

I'm very much aware, thanks for git 101 (which I'm not needing, thanks)

I think that how you think about your daily work is sometimes more important than how the software itself works. For git branches, this very much applies.

You seem to disagree, which is fine. But just because the way I usually think about things is different from how things really are, doesn't mean I don't know how things really work.

@b0rk

When that happens, I'll remember how things work technically and resolve the situation.

But for everyday work? Nope, not happening.

And yes, I *also* have git repositories with multiple root commits. Doesn't change about how I think about branches.

@b0rk @dos

Sigh.

The question is not 'how does git implement branches', it's 'how do you think of branches in git'

My answer is closest to option 1.

I know that's not how git works! But that's fine.

What you don't seem to understand is that it's perfectly possible to have a simplified mental model of how software works, which lets you get on with actual work, without getting confused when the model doesn't match reality, because you're aware that your mental model is @b0rk

So instead, I think of git branches as a set of commits that have a common ancestor with the parent branch, and which can at some point be merged back into the parent branch. That's a much more useful way to think about it, which is supported in all but unusual situations.

When I encounter an edge case in real life, I know about it enough to deal with it. That just doesn't often happen though.

@b0rk

Respectfully disagree.

The question was, how do you think about git branches.

I know that the technical implementation of a git branch is just a pointer to a single commit which can move around to other commits, with some overridable safeguards so you don't get too surprised when things are done. However, that's not a very useful way to think about it, IMO.

@b0rk

No, I don't live in Belgium anymore. So what? These things still matter.

There's a reason why chiropractors make money from mostly 40+ people